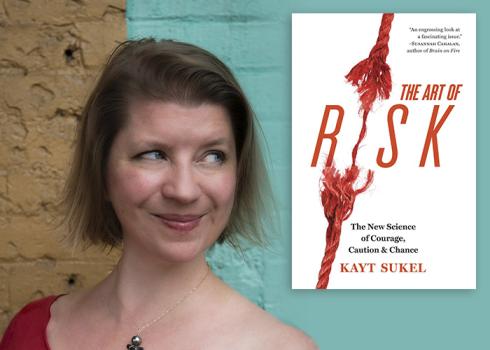

MyPath Q&A With "The Art of Risk" Author, Kayt Sukel

Author Kayt Sukel recently published “The Art of Risk: The New Science of Courage, Caution & Chance,” which looks at the science behind why people take risks and how we can all become better risk takers. She’s also the author of “This is Your Brain on Sex: The Science Behind the Search for Love.” She spoke with MyPath about her research into risk, how it affected her view of insurance, and how students can approach the risks of college.

MyPath: Insurance doesn’t have a sexy reputation, but as someone who’s now written books about risk and sex, do you find insurance a little bit sexier these days?

Kayt Sukel: I’ll admit it can be really hard to make insurance sound sexy. But I do think it’s important to take the time to really understand what insurance is and can do for you and how it can help better position you for [the fact that] the worst can—and, as we know, often does—happen. The key is not falling back on stereotypes and understanding that being prepared, and having an understanding of the risk involved in life, can actually help you better interact with the world around you. Not only to survive but to thrive.

MyPath: Did writing the book and learning about risk change the way that you insure yourself and your family?

Kayt: My mom is actually an insurance professional. She’s the type of person who is prepared for every possible contingency. A lot of us think of ourselves as very rational people. We think that we approach things logically.

Yet, when you start to look at the brain science, especially how the brain deals with uncertainty, you’ll see that the brain takes quite a few shortcuts. We humans have these three pounds of Silly Putty in our skull, and its basic job is to do one thing: predict what is coming next in the world. It is trying to really hone in on what is most important. And to do that—to move your attention around appropriately—it has to take a lot of shortcuts. It couldn’t do its job any other way.

Where I think that is important, especially when it comes to insurance, is that we see some of these shortcuts come into play with high emotion and high stress, and it really changes the way you start to think about things—and how you make decisions.

The example I give in “The Art of Risk” is the lottery. The odds of winning the lottery (there’s some ridiculous statistic) is like one in 292 million. But we start thinking about all these good feelings if we happen to buy a winning ticket. Once we start consciously thinking, “Oh gosh, when I win, I’m going to tell my boss to shove it, I’m going to help my mom buy her dream home,” we see that the brain just stops thinking about that big, messy statistic. It simplifies the calculation from one in 292 million to, “I have some chance of winning.”

That’s why it’s so important to understand these shortcuts that the brain takes. Some people get bullied by fear into an insurance policy that isn’t really going to help them, and then we have people who totally skip out on things like flood insurance when they live on the coast. Those strong feelings change the way the brain is making risk calculations. So when you understand these shortcuts, you can become better aware and have a better understanding for making decisions.

MyPath: Did the fact that your mom is an insurance professional have any sway in your decision to take a look at how we perceive risk?

Kayt: I honestly didn’t even think about it! She has always been a more risk-averse person. And she’s not a stick in the mud by any stretch of the imagination, but she likes to prepare for second-, third- and fourth-order consequences.

Her brain is always thinking 10 years down the road, and that’s how she was built. My dad was not built that way. He was always more of a fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants kind of person, and I probably take after him a bit more, but I still have her voice in the back of my head talking to me about why I’m doing the things I am doing each and every day.

So I wouldn’t say her work was a direct inspiration, but I must admit that I definitely have her voice whispering in my ear as I’m about to make any big decision.

MyPath: So your mom was an insurance professional, but in researching the book, did you have a chance to meet any risk management professionals?

Kayt: One thing I found really interesting is how much the definition of a risk manager varies from place to place. For some people, this may be a manner of doing research, more actuarial-type stuff. And for other people, it’s more of a people-management gig. It seems like there is quite a bit of variation in what a risk manager is—and what that person actually does.

In fact, I think there are a lot of people out there who, whether they know it or not, are risk managers… A lot of engineers and innovators, they’re risk managers, though they may not think so. Project managers, artists, financial professionals—they are a type of risk manager too. So, from my perspective, people don’t understand just how varied these positions can be. In the real world, there is a lot of interesting work being done concerning risk that goes across disciplines and industries.

MyPath: Another factor of that is that the only exposure young people even have to the idea is through pop culture. For instance, the movie “Along Came Polly” introduced many people to the idea of a risk manager or an actuary. Have you seen the movie?

Kayt: I have seen that movie! And I will tell you that every successful risk taker that I spoke with is a nerd to a very large degree. Now, they may be jumping off cliffs in a wing suit, setting up multimillion dollar business deals, or sitting on the final table of the World Series of Poker, but they all are nerds in their own ways.

I take issue with the idea that being nerdy is somehow bad or uncool, because I think that there’s a lot of benefit to being prepared and to being thoughtful, no matter what you do for a living. So much of it isn’t really trying to remove risk altogether but really trying to understand what factors are most important to good decision making. What do you really have to focus on? How can you best ignore the distractions that are going to get in the way of your reaching your end goal?

I think we do ourselves a disservice when we decide that nerdy is a negative. There’s a certain level of analysis, which is really important for success in life overall. And that kind of preparation doesn’t require Poindexter glasses and a bow tie. And even when you do get down into the nitty gritty, you find that risk analysis is really a fascinating topic, whether you approach it from a big data perspective or from a more granular level.

MyPath: To that point, was Ben Stiller’s character even a good risk manager, given that he simply wanted to avoid every risk possible?

Kayt: I don’t know that the movie gives you a really good idea of who he would be at work. I get the feeling he would maybe be the guy that everyone is rolling their eyes at in meetings, telling them why you can’t do your project in any which way because every method is imperfect.

That’s the thing. Every situation, every way forward, is going to be fraught with some kind of risk. There are always going to be potholes along the way. The trick is being able to look at the field and understand which potholes are maybe just going to trip you up a little bit and which ones are filled with quicksand and really going to stop you from reaching your long-term goals.

MyPath: One part of life that’s filled with potential potholes is college, which involves not only what we traditionally think of as risk, like excessive partying, but also life-changing decisions, like picking a major. Any advice for college students trying to better manage risk?

Kayt: I think that you need to give yourself some room to fall down and make mistakes. There needs to be a certain amount of room for forgiveness, whether you’re talking about the partying [and] the social aspects or…your college major or other big life-deciding stuff. Because in many cases, this is an individual’s first opportunity to be out on [their] own, to figure out how to manage [their] own time, to figure out what [they] want to do with [their] life.

So, like any risk, it is a matter of being self-aware and really conscious of it. What are you really there to do? It’s not to do keg stands and party every night. It’s to get an education. But it’s also learning your limits—learning how to problem solve and to balance. It’s learning how to have a social life without having everything else fall through the cracks. It’s an important skill to learn.

You need to understand that there may be some times where you make mistakes, and as long as you learn from them and keep moving yourself forward toward that end goal—getting a degree—then you don’t have to be that hard on yourself.

In terms of picking a major, you have to experiment. Don’t be so quick to say that you shouldn’t be taking that art class. A single class isn’t always going to change up whether or not you want to be an engineer, a writer, or a computer programmer, but it might give you a different way to think about different problems. It may give you a different approach. And that’s invaluable.

I love universities and colleges that give you enough room where you can take different classes so you can directly experience all of those different points of view and understand how other majors are working, because you may figure out at the end of year one that, wow, engineering really isn’t your thing. You really want to go into physics or something else. It may be a chance encounter in a chance class that sort of gets you thinking in a different way—and changing the way you see your future.

MyPath: What are you planning to tell your kids about handling risk?

Kayt: One thing parents have gotten really bad about, especially in the United States, is trying to protect our kids from failure. Everybody has to get a trophy, we tell people that they are great at everything even though they are not. We need to have the ability to let kids fail and let them mess up but then really teach them how to fail forward: “OK, you know what, this is not your thing, but what can you learn from this?” or “Just because this didn’t work out, it doesn’t mean you’re done. What can you apply going forward to either do it better next time or put [yourself] on a different path?”

Helicopter parenting and trying to make it so kids never have to face the consequences of their mistakes really puts them at a disadvantage. Risk isn’t about never messing up. Risk is part of every decision we make every single day, even the most seemingly inconsequential ones. It’s a matter of teaching our kids how to deal with the uncertainty, to learn [their] limits, to learn how to problem solve, work with others, and work hard toward [their] goals.

Kids can’t always have somebody outside protecting them from risk, the world, or the consequences of any errors. They need to figure out how to manage it on their own.

MyPath: From your research, what’s something that most people think is risky but you no longer think of in that way? And vice versa, what’s something that most people don’t think is risky but you now think of as a bigger risk that people should take into account?

Kayt: I’m going to answer the second part of your question first. Driving in your car every day.

Most people don’t think much about even an hour to an hour-and-a-half commute in a car on the freeway. It’s nuts that we are so cavalier about it. Sometimes on the highway, I will look around and think, “OK, which one of us in this group is going to end up in the accident today, because odds say it’s probably going to be one of us.” Of course, that’s probably a good call for car insurance.

So much of what we think of as risky or not risky comes down to what we have experience with. So often, people want to talk about risk in terms of these extremes—for example, extreme sports and these crazy Wall Street business deals and gambling. But really, for those folks who live these lives and are really invested in these kinds of careers, it’s not that risky for them. And that’s because they’re prepared. They do the homework. They aren’t impulsive. They have the experience, so they really can ignore a lot of those distractions—the things that keep the rest of us weirded out and up at night. I still look at these people with awe, but I also still understand how much of it really comes down to being prepared and doing the work.

MyPath: What is your general advice to people who ask you, “What’s the best way to be a successful risk taker?” or “What are the similarities of successful risk takers?”

Kayt: Ironically, all of the successful risk takers that I have spoken to gave me some version of, “I’m not a risk taker,” which I thought was pretty funny. These are people who plan enemy incursions or jump off cliffs, so it was kind of fascinating to me that they felt that way.

A lot of it is knowing yourself. Some of us are wired to [be] more impulsive. Understanding that about yourself is important, because you can really sort of think about why you are approaching different situations in certain ways.

The second step comes to being prepared and doing your homework. Once you get in and you really look at the numbers, you understand the ins and outs of that situation. Whether it is climbing a 1,000-foot peak with no rope or…figuring out if you need flood insurance, you need to be prepared. Doing so gives you the ability to read the scene and understand the right questions to ask. It lets you focus on the right factors instead of being distracted by things you don’t understand. And it puts you in a position where you can make a much more informed decision.

MyPath: Anything else about risk that people should know?

Kayt: The big thing I’d like to point out, going back to where we started, is that we really are burdened with this idea that we are always rational, logical beings. One of the beauties of neuroscience, or these new ways that we are exploring our understanding of human behavior, is that it gives us a different lens to view things. It’s not that we’re so much crazy or impulsive or what have you. A lot of it is just the brain trying to make sense of the world around you and trying to take some shortcuts to get you to the endpoint faster. But you have to ask, What got left on the cutting room floor as it did so?

When you are especially talking about risk management with any kind of human element, understanding the brain sciences is going to become increasingly more important. Otherwise, you are just standing there saying, “Wait a minute, it should have gone this way,” or “Why did this deal do a complete 180?” More often than not, the answer to those questions is going to be easier to figure out when you really understand more about the science, particularly the neuroscience, behind decision making.